Leaders, relax don't do it!

Responding Intentionally – Moving From Reacting to Responding

How leaders react—or respond—is perhaps the most consequential behavior they

perform. Depending on the reaction, the tone or emotion expressed, and the

words that are used, right or wrong decisions will be made, people will be

inspired or alienated, and business results will be good or bad.

Reactions are immediate and fraught with emotions. Responses are thought-out

and intentional. When leaders manage and respond with intent, better decisions

are made, relationships are strengthened, and collaboration and team health is

reinforced. In turn, their organizations are healthier and more productive.

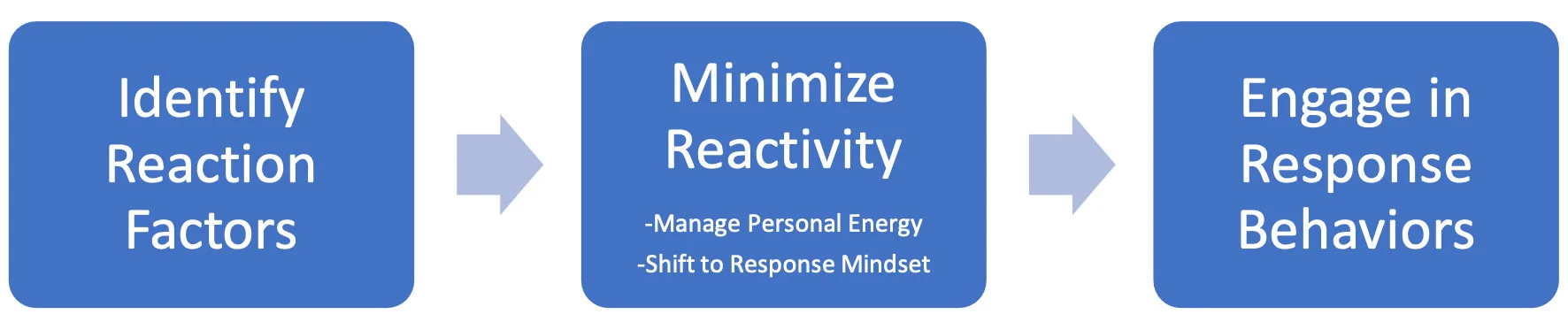

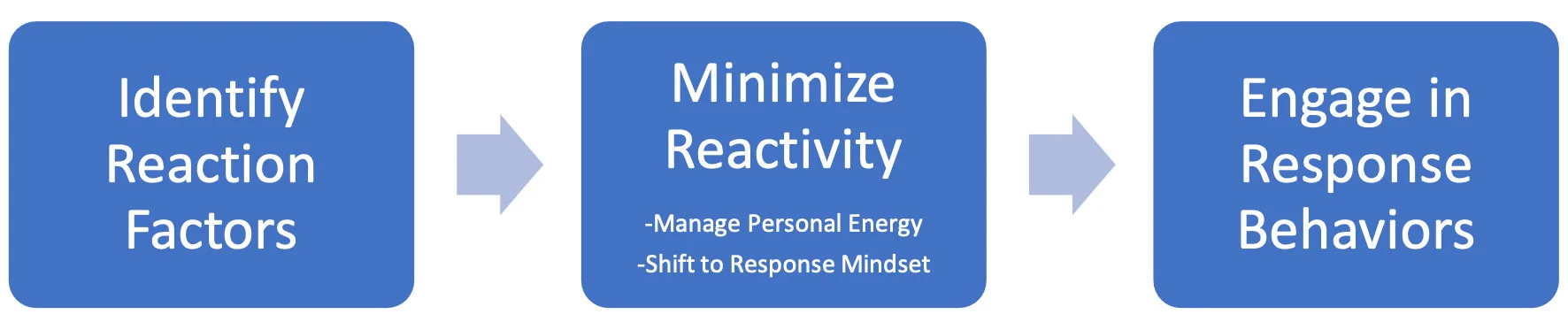

So what can leaders do to ensure they are responding and not reacting? The

Skyline Intentional Response Model calls for:

1. Identifying your Reaction Factors

2. Minimizing Your Reactivity

3. Engaging in Response Behaviors

The Intentional Response Model

In this paper, we outline the model and show how you can increase your ability

to respond with intention in even the most stressful situations.

Identifying Your Reaction Factors

According to Ruven BarOn, there are five main components that make up

emotional intelligence (EQ): self-perception, self-expression, interpersonal,

stress management, and decision-making. It is easy to see how the ability to

respond intentionally and engage in response behaviors can up your EQ in all

five of these areas, but particularly as it relates to stress management and

decision-making. Having a high EQ is more than just knowing yourself,

expressing your feelings, and being able to relate to others. It’s also about

being optimistic, controlling your first impulses, and having a high stress

tolerance so you can effectively solve problems under threat.

Neuroscience has taught us that the brain is wired to minimize threat and

maximize reward. That is to say, our automatic reaction to any situation

depends on whether we perceive it to be a threat or an opportunity.

If we perceive a threat, our flight-or-fight response is triggered. Examples

of this are shoving someone if he or she steps too close into our personal

space and make us feel uncomfortable (fight response) or stepping backwards to

get away from them (flight response). Both actions are automatic and

immediate.

The same flight or fight response occurs within social interactions. If we

perceive a threat to our social wellbeing, we react automatically to preserve

our sense of self. However, this reaction—immediate and emotional as it is—

is not always the best course of action in the long term, especially if the

perceived threat wasn’t a threat at all.

Each person also has his or her own reaction factors that increase or decrease

his or her reactivity to perceived threats. The perception of threats varies

from person to person. There are universal threats like physical harm and

danger. In the work environment, the perception of what is a threat is

individualized. Threats to survival can include threats to your status;

therefore, it can impact a number of things from your likelihood of promotion

or others’ willingness to work with you. Personal reaction factors are

informed by your personality, past experiences, background, upbringing, and

education.

The severity and impact of these threats can also be easily triggered when

one’s resilience is lowered. This can occur in one or all of the following

areas: mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional. Your reactivity increases

if you are feeling deficient in any of these areas (e.g.,, if you are tired,

sick, feeling unfulfilled, or dealing with a loss in another area of your

life).

Knowing how and when you are compromised and therefore less resilient is an

important factor in maintaining your resilience so you are less likely to get

triggered. On top of that, knowing the drivers that can trigger a threat

response can increase your awareness and help you modify your reactions when

necessary. Awareness is the first step; minimizing your reactivity is the

second.

Minimizing Your Reactivity

Think of a situation in which you have acted impulsively. How did you react?

How would you have responded if you hadn’t felt threatened? Which reaction

factors were in play? How can you minimize them so you don’t see a similar

situation in the future as a threat? The answer is by boosting your

resilience.

According to Diane Coutu, resilient people possess three defining

characteristics:

1. They coolly accept the harsh realities facing them (they are calm, not

triggered)

2. They find meaning in terrible times (they are rational, not emotional)

3. They have an uncanny ability to improvise, making do with whatever’s at

hand (they respond intentionally, not react emotionally).

Resilience, Coutu writes, is “merely the skill and the capacity to be robust

under conditions of enormous stress and change.” And the key to boosting your

resilience is managing your energy—that is, ensuring that mental, emotional,

spiritual, and physical reaction factors are not in play.

Managing Your Personal Energy

According to Tony Schwartz and Catherine McCarthy, “By fostering deceptively

simple rituals that help employees regularly replenish their energy,

organizations build workers’ physical, emotional, and mental resilience.”

The authors offer the following tips to manage your personal energy on a

regular basis. Then when a situation arises that could trigger a threat

response, your reactivity is low, and resilience is high.

Physical Energy: Your physical energy is enhanced by getting enough sleep,

engaging in regular cardiovascular activity, eating to satiety, and taking

regular breaks from sitting at a desk.

Emotional Energy: Your emotional energy is renewed by fueling positive

emotions in yourself and others, for example, by expressing appreciation for

others and gratitude for what is going well in your life. In the moment, deep

abdominal breaths are helpful for defusing tense situations and calming down.

Mental Energy: Your mental energy is supported by removing distractions and

interruptions from your daily work, allowing you to focus completely on the

task at hand. It is also helpful to identify your top priority each day (or

the night before) so you can start the day with focus and intention.

Spiritual Energy: Your spiritual energy is replenished by making time for

those activities that give you feelings of “effectiveness, effortlessness,

absorption, and fulfillment,” in other words, that put you in flow. Allowing

the time and space for the activities you enjoy and that you value the most is

key to feeling in alignment with your spiritual self.

In the moment, there are also several actions you can take to lower your

reactivity and not feel so threatened. These include taking deep breaths to

calm your nervous system, physically removing yourself from the situation, and

taking a walk. These actions give shifting to a response mindset.

As part of how you respond to a situation and the energy required, take into

account that you have a choice for whether to react or not react. Not all

circumstances and situations require a reaction or a response. Prioritizing

what and how you respond will allow you to make an intentional decision to

expend the resources (time, energy, etc.) required to respond.

Shifting to an Intentional Response Mindset

To respond intentionally to a stressful situation, your brain needs to see the

situation as unthreatening. This requires a mindset shift. As Schwartz points out,

“Expectations shape reality.” If you expect a threat, you’ll see a threat. If

you expect an opportunity, you will see an opportunity. Therefore, a mindset

of growth and opportunity is necessary.

You can begin to shift your mindset by exploring the differences between

growth and fixed mindsets. People with fixed mindsets have a very inflexible

sense of self. For them, any comment or action that is not aligned with that

rigid sense of self is likely to be seen as an attack. Therefore, they react

by protecting themselves. They can appear angry, defensive, or even

territorial. On the other hand, people with growth mindsets see themselves as

continually evolving and improving. They first perceive situations through a

lens of growth and opportunity—how can I take what is being said or done and use it to improve myself? Instead of seeing feedback as highlighting their deficiencies, they see feedback as a learning opportunity.

Challenge your ability to adopt a growth mindset by asking yourself and

working diligently on the following questions and constructs:

- How can I depersonalize the communication (i.e., not see it as an attack on my sense of self)?

- How can I separate the person from what is being communicated (i.e., let go of my personal views of the communicator)?

- How can I use what is being said or done to improve myself?

- What can I learn from this?

By taking the time to set up your mindset and corresponding behaviors to

respond appropriately, you will begin to move from a place of reactivity into

an intentional response mindset.

Engaging in Response Behaviors

Once you are in the right mindset, you can engage in a situation in a

thoughtful and productive manner that moves the situation forward and

maximizes beneficial results for all. You can show your resilience. You can

stretch your emotional intelligence (EQ).

While each situation will require different actions, here are a few universal

steps you can take to ensure the other people involved are also operating from

an intentional response mindset.

First, share your emotional state and what you are thinking. Make a personal

connection by revealing a bit about yourself. This will deescalate the threat

response in the other person.

The next steps have to do with showing your resilience, which Coutu states

consists of:

1. Facing down reality – taking a sober, down-to-earth view of the situation.

2. Find meaning – searching for ways to make this perceived hurdle a building block to something better.

3. Being inventive – collaborating and brainstorming to spark solutions and energize the team.

Conclusion

Reactions are immediate and fraught with emotions. Responses are thoughtful

and intentional. When leaders manage and respond with intent, better decisions

are made, relationships are strengthened, and collaboration and team health is

reinforced. In turn, their organizations are healthier and more productive.

These types of leaders are said to be resilient and to have high EQ.

About Skyline Group

Skyline Group is the leading provider of scalable leadership solutions

including leadership coaching, our superior 360 assessment, and leadership

coaching technology - C4X. Launched in 2012, C4X is the only coaching solution

that gives you the ability to develop all of your leaders consistently and

systematically. Learn more at SkylineG.com and C4X.com.

References:

1. Talent Assessment Portal. The EQ-i 2.0 Model and The Science Behind It.

Retrieved from https://tap.mhs.com/EQi20TheScience.aspx

2. Gordon, e. (2000). integrative Neuroscience: Bringing together biological,

psychological and clinical models of the human brain. Singapore: Harwood

Academic Publishers.

3. Scwartz, T. and McCarthy, C. (2015, July 16). Manage Your Energy, Not Your

Time. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2007/10/manage-your-energy-not-your-time

4 Coutu, D. (2016, July 11). How Resilience Works. Retrieved from

https://hbr.org/2002/05/how-resilience-works

5 Dweck, C. (2014). The power of believing that you can improve. Retrieved

from

https://www.ted.com/talks/carol_dweck_the_power_of_believing_that_you_can_improve